Zach Blas

Contra-Internet Aesthetics

Proliferations of discourses that are decidedly ‘post-’ inundate artistic and intellectual life today: a post-Fordist mode of production gives way to post-politics and post-capitalism, which is accompanied by a post-media, post-digital, post-internet landscape populated by post-identitarian post-humans that are post-feminist, post-race, and post-queer. It is an era that, easily enough, has been summed up as post-contemporary, and not so long ago, postmodern. Such a postal deluge Donna Haraway has aptly described post-onslaughts 7 as going postal. See: When Species Meet (Minneapolis: Recall the 2013 US National Security Agency surveillance revelations exposed by whistleblower Edward Snowden. University of Minnesota Press, 2007). encourages the question: what is this prefix that stretches across the world to account for myriad global conditions? If ‘post-’ is commonly used to signal an ‘after’, then what does its excessive use convey about the historical present? Are we ‘after’ everything, supplanted in endless, elusive passings, a never-ending fractal vortex, where post-isms spin past all horizons to infinity?

Uses of ‘post-’ appear to contain contradictions: in a time of political upheaval and revolt, we are post-political; in a time of digital domination, we are post-digital; in a time of ever-rampant homophobia, misogyny, racism, nationalism, and transphobia, we are post-identitarian. Yet, deployments of ‘post-’ do not simply mean an after, but also illustrate saturation or (pseudo)totalization. For example, post-identity conceptions like post- feminism, post-queer, and post-race are attempts to understand subjectivity and the body beyond identity-based strictures that have been wielded to subjugate persons, while post-medial formations address a far-reaching penetration of digitality that permeates life and culture. Undoubtedly, ‘post-’, as a heterogeneous assemblage, reigns with immensely varied politics and vastly differing temporalities. It is strikingly dissimilar from periodizations like the disciplinary and control societies. ‘Post-’ drifts between eras, politics, peoples, and practices, while it still designates periods and passages of time. With such overuse, can ‘post-’ function as a unified designator of anything, let alone have a unified aesthetics or politics? Of course, the decision to use ‘post-’ as a discursive frame is ultimately a political act. From that perspective, ‘post-’ communicates a haziness or murkiness—a blanket generalization that is an empty descriptor. ‘Post-’ announces that challenging instances of passage and transformation can only be articulated through what they proceed. But is this enough? Is ‘post-’ not more of a stylistic convenience that evinces a blind spot, an inability to account for the present in its specificity and singularity? Is it not an easy shorthand for what could be called an impasse to think the contemporary?

As an artist and writer engaged with art, media, technology, and politics, I would like to zoom in on post-internet aesthetics, a term with much affinity to theories of post-media and post-digital, but one that directly concerns current artistic practices. Post-internet art and aesthetics popularly stands for an array of artistic production that emerges from the (ostensible) indelibility of internet technologies and cultures, and thus implies that the present is a time in which the internet has thoroughly permeated artistic production. As such, post-internet aesthetics would seem to account for a widely and wildly divergent grouping of people and practices, but it is rather taken up by a considerably moderate collection of hip, young, ‘digital native’ artists and art institutions mostly in the West, a reality that contradicts its temporally totalizing implications. If we are post-internet, what art is not post-internet? Yet, within this category, there are fine, stand-out artists, who are not necessarily at issue. Mine is a structural concern: post-internet aesthetics, as one symptom of many within our contemporary postal disorder, does not escape the nullifying force of that marker, which reduces the concept to a generic descriptor—a pseudo-totality that does not account for variation and difference. This is the seduction of post-internet aesthetics to art markets and commercial vectors: its neutral frame provides a safe, hollow concept to fill, which corrupts the very political potential of aesthetics My approach to aesthetics is adapted from Jacques Rancière’s writing. See: Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006)., as what can intervene and shift conditions of life towards equality, not capital. At its worst, post-internet aesthetics is just the latest cool media art episteme or distribution of the sensible. At its best, it can only be the broadest of starting points for understanding and experimenting with the present.

If post-internet aesthetics is on its way to becoming an ascendant category for digital, net-based artistic practices Consider frieze magazine’s 2013 survey of art after the internet, which featured my own artwork and partially inspired this essay, as well as the 2013 ‘Post-Net Aesthetics’ panel at the ICA London. See: ‘Beginnings + Ends’, frieze, Issue 159, November-December 2013, and ‘Post-Net Aesthetics’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, http://www.ica.org.uk/whats-on/post-net-aesthetics., this is troubling for artists invested in political struggle, transgression, and subculture (which, to be clear, is my position), because it dilutes radicality and militancy through its nebulousness and temporal, technical determinism. I feel ‘post-‘ is an insufficient choice for articulating political and aesthetic alternatives both within the internet and digitality. Instead, the alternative asks: what is after, before, or beyond ‘post-‘? What are the transversal forces that cut through ‘post-’ and disallow easy designators of time and technics to account for conditions of globalization?

Today, as digital networks and information technologies increasingly operate as tools of control, surveillance, policing, and criminalization, a political demand extends to us, insisting on the refusal and reconstitution of these militarized systems. As such, politico-aesthetic practices that respond to this demand require an equally radical conceptualization. Thus, if post- internet is inadequate to militant and revolutionary gestures, what is?

We can begin seeking initial answers to this question by reading post-internet against itself, as what comes after the internet and not its totalization. This is a strategy similar to feminist theorists J. K. Gibson- Graham, whose designation of ‘postcapitalist politics’ describes alternatives already in existence within the supposedly totalized frame of capitalism. In this instance, post-internet would convey both an abandonment of the militarization and control of the internet for the construction of political alternatives to digital networking. This is what media theorists Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker have called the ‘antiweb’ Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker, The Exploit: A Theory of Networks (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007) 22.—autonomous networks that are exoduses from the internet. Examples include mesh networks, darknets, and surveillance evasion devices.

I would like to suggest that the artistic militancies and political subversions of the internet are not post-internet aesthetics but rather contra- internet aesthetics. I take ‘contra-‘ from the queer and gender theorist Beatriz Preciado’s Manifesto contrasexual See Beatriz Preciado, Manifesto contrasexual (Madrid: Anagrama, 2011)., in which contrasexual is defined as the refusal of normalizing power structures that produce sexuality and gender through a patriarchal, heterosexist, capitalist framework. Contrasexual rejects the simple categorization of man and woman as naturalized entities and instead articulates a counter-sexual position: a being-against that posits all sexes and genders as technologies that have been produced through power. Consequently, contra-internet aesthetics considers the internet to be swelling from the same normalizing systems of control that Preciado rails against; indeed, contra-internet aesthetics recognizes that the internet is a premier arena of control today, bound to mechanisms that vehemently and insidiously police and criminalize non-normative, minoritarian persons: biometric regulation, drone attacks, and data mining sweeps, to name but a few. Contra-internet aesthetics disallows the internet to determine its horizon of possibility. But just as contrasexual and contra-internet are assaults against normalization and oppression, they also insist on alternative forms of understanding, pleasure, knowledge, and existence. Thus, as contra-internet aesthetics could strive to bring the internet to ruins, it does so to create positive alternatives.

The coming contra-internet aesthetics involves:

1. An implicit critique of the internet as a neoliberal agent and conduit for labour exploitation, financial violence, and precarity.

2. An intersectional analysis that highlights the internet’s intimate connections to the propagation of ableism, classism, homophobia, sexism, racism, and transphobia.

3. A refusal of the brute quantification and standardization that digital technologies enforce as an interpretative lens for evaluating and understanding life.

4. A radicalization of technics, which is at once the acknowledgement of the impossibility of a totalized technical objectivity and also the generation of different logics and possibilities for technological functionality.

5. A transformation of network-centric subjectivity beyond and against the internet as a rapidly developing zone of work-leisure indistinction, social media monoculture, and the addiction to staying connected.

6. Constituting alternatives to the internet, which is nothing short of utopian.

Glimpses of contra-internet aesthetics can be seen in

Jemima Wyman

Jemima Wyman, Space for Cryptic Powers, 2013 ’s tactical camouflage works, where protest, pattern, and feminism

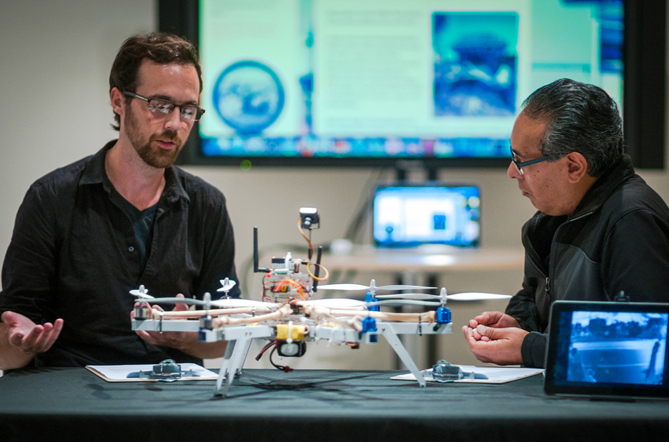

collide; Ian Alan Paul and Ricardo Dominguez’s staging of a

drone crash

Ian Alan Paul,

Drone Crash Incident: Town Hall Meeting

, 2012, Calit2 Gallery, University of California San Diego

at the University of California San Diego to instigate public discussion

on drone ethics and violence; micha cárdenas’

Local Autonomy Networks

Ian Alan Paul,

Drone Crash Incident: Town Hall Meeting

, 2012, Calit2 Gallery, University of California San Diego

at the University of California San Diego to instigate public discussion

on drone ethics and violence; micha cárdenas’

Local Autonomy Networks

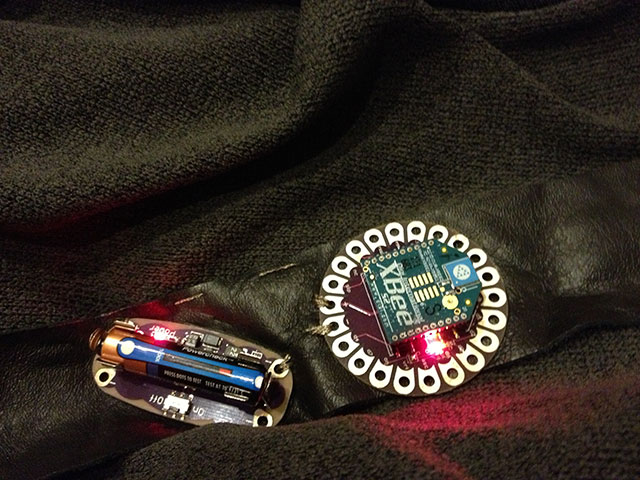

micha cárdenas,

Local Autonomy Networks/ Autonets, Mesh Networked Bracelet,

2013 , which uses mesh networking to promote transformative justice and

anti-violence activism for queer, transgender people of colour; Dan

Phiffer’s Occupy.here, a darknet designed for Occupy activists; Hito

Steyerl’s meditation on resolution, control, and digital technologies in

the video

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking didactic Educational .MOV File; and

Electronic Disturbance Theater’s Transborder Immigrant Tool, a

mobile phone equipped with GPS that aids persons attempting to cross the

Mexico-US border locate water caches and help centres.

I would also like to situate my own artistic practice within this

aesthetic demarcation, from my earlier project,

Queer Technologies, to the ongoing

Facial Weaponization Suite

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite, 2011-14, a series of mask workshops in which collective masks are produced

from the aggregated biometric facial data of participants. The masks

function as both a practical evasion of biometric facial recognition and

also a more general refusal of political visibility, which intersects

with contemporary social movements and their use of masking. The first

mask in the suite is Fag Face Mask, which is a critical

engagement with recent scientific studies that claim sexual orientation

can be determined through rapid facial recognition techniques. The

second mask addresses a tripartite conception of blackness, split

between racism (citing biometrics’ inability to detect dark skin), the

favouring of black in militant aesthetics, and black as that which

informatically obfuscates.

In her manifesto, Preciado invents dildotectonics as a ‘contra-science’

that demonstrates the possibilities of contrasexuality. For her, the

artificiality of the dildo points toward gender and sex as technologies,

and also operates as a resistant tool against normative productions of

bodies and pleasure. Preciado explains that dildotectonics turns the

body into a dildoscape—a zone of contrasexuality, and she develops a

series of experimental practices to achieve this. What, in turn, is the

dildo of the internet? Its fibre optic cables, government backdoors,

wireless routers, or spambots? Where are the net-dildos that make

intelligible the internet’s complicity with control, subjugation,

surveillance, and political violence? Certainly, the previously

mentioned artworks are each a net-dildo that uniquely contra-fucks the

internet. A key contra-science these works share is an investment in

informatic opacity, a tactics of withdrawing from control by evading

detection or interception from the commercial internet: darknets and

mesh networks are informatically opaque in that they share information

through anonymity and function with autonomous technical infrastructure.

Tactics of camouflage, like masking, make persons opaque to digital,

networked surveillance.

Informatic opacity

Zach Blas,

Facial Weaponization Suite: Fag Face Mask

,

20 October 2012, Los Angeles, CA., then, is best understood as a prized method of contra-internet

aesthetics.

While

contra-internet

Zach Blas, Jubilee 2033, trailer, 2014-18

aesthetics can be concretely experienced through a growing constellation

of artistic practices, it also must exist as an ideality: as the

aesthetic potentiality to make the political alternative. This demands

an inexhaustible openness, as something not fully known but sensed—a

longing, the fantasy of a future. Thus, the promise of contra- internet

aesthetics is a utopian horizon that calls forth another network—one

that is not ‘post-internet’ but rather ‘contra-’.